By: Siyi Chu and Harshvi Trivedi

Gargi Mishra is a 21-year old Teach for India fellow teaching in a low-income private school in Shivaji Nagar, Govandi, Mumbai.

Terri Place is the founder and director of The Baobab Home, which for the past 15 years has been providing aid and education to underserved children in Bagamoyo, Tanzania.

Though located an ocean apart and in communities with diverse needs, since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Gargi and Terri have been sharing a common battle. Both have seen the children they serve grapple with a wide range of issues induced or exacerbated by the pandemic, and both have had to come up with new strategies to cope with the challenges.

“The first wave hit us on March 18th, 2020, when a Tanzanian person came back from Europe infected. All the government schools shut down almost immediately. We had to close too.” A major component of The Baobab Home’s services is a private elementary school called the Steven Tito Academy, so school closure is the first thing that comes to Terri’s mind when speaking about challenges during COVID.

Loss of learning is also on the forefront of Gargi’s mind, who is particularly concerned about inequity in access, “A lot of kids I work with have ended up falling through the cracks in terms of their learning because of the pandemic. It was so heavily dependent on who has access and who doesn’t.”

Such a plight shared between Terri and Gargi is not unique to them: the children they work with are among the 1.6 billion children and youth affected by school closures globally, according to a resource made available by UNICEF, which also highlights that 463 million children globally are not reached by digital and broadcast remote learning, amounting to a third of the world’s school children. Other than learning loss, this resource touches upon a wide range of issues – from poverty to nutrition to violence, providing a birdseye view of the circumstances of children worldwide during the pandemic, including those in communities like Bagamoyo and Shivaji Nagar.

Here, with the aid of UNICEF’s data resource, we dive into Terri and Gargi’s experience through COVID to take a peek at some of both the risk and protective factors surrounding children through this special time.

Everything Trickles Down to Affect Children

“All children, of all ages, and in all countries, are being affected,” The UNICEF data resource COVID-19 and Children analyzes, offering a two-tiered attribution of factors affecting children’s wellbeing: “in particular by the socio-economic impacts and, in some cases, by mitigation measures that may inadvertently do more harm than good.”

Indeed, both Terri and Gargi have named trickled down socio-economic impacts among the top of their concerns.

During the pandemic, Tanzania has seen a sharp drop in tourism, the nation’s second-largest foreign exchange earner after gold. Natural Resources and Tourism minister Hamisi Kigwangall has predicted a 77% drop in earnings and a 480,000 tourism job loss due to COVID. “Economically, the whole country is just impacted, no matter where you are,” Terri shares, the families she works with being no exceptions.

In Shivaji Nagar, families have faced livelihood losses so huge that not only are they struggling to afford tuition, children often have to be enlisted as helping hands in order to maintain household income.

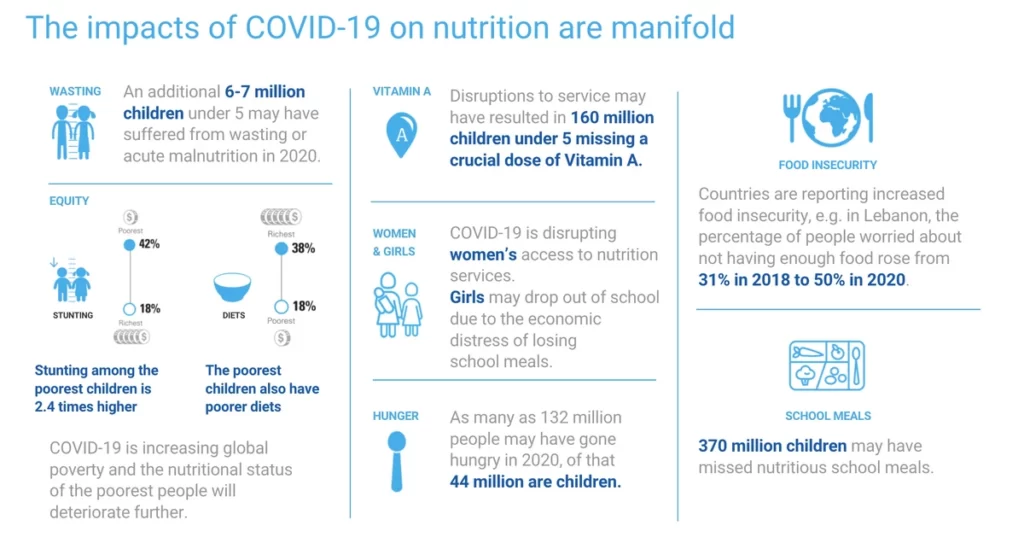

Globally, too, child poverty is on the rise. According to the resource, the percentage of children living in multidimensional poverty globally, based on access to education and/or health services, has risen from 47% pre-COVID to an estimated 56%.

Schooling During School Closures

School closures, on the other hand, are among the other type of factors mentioned by the UNICEF resource above. Enforced as a necessary measure to reduce the transmission of COVID, school closures, however, inevitably disconnect children from the one institution they rely on most heavily. The impact, therefore, is multifold.

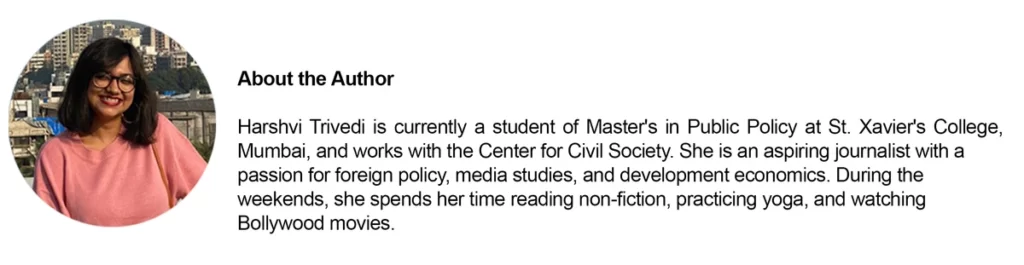

Loss of learning alone, as both Terri and Gargi have touched upon, is a lot to deal with. To make up for it, schools and teachers around the world have had to adapt to new modes of instruction. “Online platforms and TV were the most used remote learning methods, offered in 90 percent and 87 percent of countries, respectively,” according to results from the Survey on National Education Responses to COVID-19 School Closures conducted jointly by UNICEF, UNESCO, and the World Bank, as listed in COVID-19 and Children.

However, even remote learning itself poses challenges, especially when it comes to differentiated access. “I work with kids from low-income backgrounds who do not have access to technology and the basic amenities.” Gargi shares, “It was very, very difficult for us for the first couple of months to just get all our kids to have access to technology so that they can access learning.” Gargi’s team worked on providing second-hand smartphones and doing internet recharges to help with the technological gap.

The situation is further complicated when teachers’ capacity is taken into account. In Gargi’s community, some teachers, herself included, are willing to go the extra mile to prepare both synchronous and asynchronous content, going into the community to deliver physical worksheets when necessary. However, due to lack of bandwidth or mindset blocks, some other teachers find it difficult to shift away from the traditional pen and paper teaching methods.

As the pandemic currently worsens in India, teachers like Gargi, along with the students and parents they work with, will have to continue coping with this new reality of education.

In Tanzania, schools have suffered less closure, which means that students didn’t have to lose as much face-to-face learning time. However, the early reopening could only be understood as bittersweet, as it is partly due to the Tanzanian government’s denial stance against the second wave of COVID. The Baobab Home only had to close the Steven Tito Academy from March to June in 2020, but that still called for a change in strategies.

Since computers and the internet are largely inaccessible in Bagamoyo, online learning, the most used remote learning method during the pandemic per the survey above, was not a possibility for children Terri worked with. The remote learning strategy here stuck to the “old-fashioned,” combining phone instructions and homework delivery.

Each teacher at the Steven Tito Academy had 25 students to call to deliver the lessons of the day. Luckily, the strong support from donors through this difficult period has enabled The Baobab Home to not only pay teachers consistent salaries but also to offer extra credits to top off their phone bills. Meanwhile, Mugi, the organization’s driver, rose as the hero to the operation of delivering homework. Every morning, he would take off on his motorbike, covered head to toe in protective gears. First stopping at the shop to print out the materials the teachers requested, he would then run all around the Bagamoyo area to make sure students received them. The dust trails of his motorbike strung together the 8 to 10 clusters of all 160 students scattered across town.

Through this collaborative, if laborious, operation, students at the Steven Tito Academy were able to get as much out of the remote learning experience as possible. What’s also important is that these individualized modes of contact have become opportunities for teachers and organizations to check in on other aspects of children’s lives.

Making up for Other Roles that Schools Play – Nutrition, Community, and Shelter

When a school closes, students face not just a loss of education, but also of everything else that the school embodies and provides. For example, according to UNICEF as reported in COVID-19 and Children, 370 million children may have missed nutritious school meals.

Terri has definitely been concerned about nutrition. Located on a large farm on the outskirts of Bagamoyo, The Baobab Home has been providing students with nutritious lunches with produce grown right on the farm whenever school is in session. When Mugi first started delivering homework, Terri took the opportunity to conduct a survey on what the families needed and how The Baobab Home could help them better. As a result of that initiative, along with the homework, Mugi has also been delivering seeds and fertilizers – giant bags of biogas manure – to families who requested so that they could be a bit more self-sustainable with food.

Another often overlooked important role that schools play, as Gargi points out, is to provide community and environments for self-expression. On one hand, “A lot of kids in my class don’t feel like they belong in a very academic-oriented setting, but they are able to express themselves much better in an extracurricular space,” while extracurricular activities have taken a big hit as schools are no longer in session. On the other hand, “Online classes are very isolated, so the whole idea of being in a classroom and feeling like they’re part of a community has completely gone. Especially for young kids, having fun with their friends has completely been taken away from them.”

Other than the active services and space they offer, schools also often function as shelters that keep children away from influences that could harm their development.

For some children, not being able to go to school means more time spent on the streets. Serving a community with substance abuse-related issues, Gargi is concerned about children becoming more likely to be led astray by such bad influences, simply “because they don’t have anywhere else to go” other than roaming in the community.

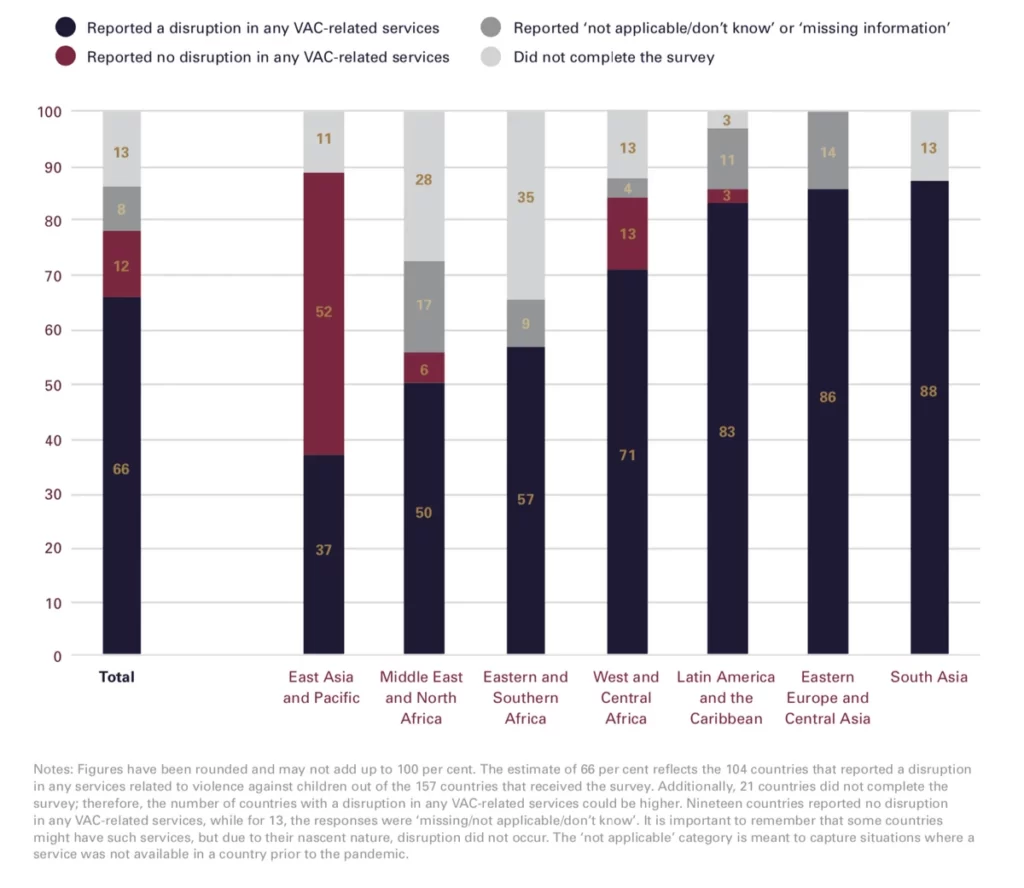

Even for children sheltered at home, they are sometimes nonetheless in increased contact with various risk factors: “heightened tensions in the household, added stressors placed on caregivers, economic uncertainty, job loss or disruption to livelihoods, and social isolation. These are well-known risk factors for violence at home. And as the risk of violence against children has increased due to the COVID-19 pandemic, child protection services have been weakened due in part to measures implemented to control the spread of the virus.” States the COVID-19 and Children resource. 66% of countries have seen interruptions to violence against children-related services.

In Tanzania, physical, sexual, and emotional violence against children has been common even before COVID. The Tanzanian government has instituted a program through which teachers are trained to teach kids to report if and when they are being violated at home. At The Baobab Home, staff has been adapting that to be as child-friendly as they could and encouraging kids to open up and talk. “We do group feeling sessions where kids can feel a little bit safer to report.” Terri introduces. In the last feeling session they hosted, children were able to open up a lot and talk about what was going on at home. “One of the girls shared that because of how coronavirus has impacted her family economically, her mom had to leave her alone at home in order to work and make money. Through that, we were able to identify her vulnerable situation, and now we’re trying to keep her safer.”

Often considered safe from contracting the virus, children are sometimes forgotten in the conversations regarding the pandemic. While resources like COVID-19 and Children help make sense of the various ways children are impacted by bringing light to the big picture perspective, the experience of and actions by people like Terri and Gargi who work right on the ground are what enlivens the numbers.

Looking ahead at the next phase of their work in Shivaji Nagar and Bagamoyo through and post COVID, both Gargi and Terri have big plans.

Gargi is running a fundraiser to reopen the community center as soon as possible, as a safe space for learning. In the long term, she wishes for the center to provide space and opportunities to address various needs identified through the past year: parenting workshops, conflict resolution, anger management, social-emotional learning, access to extracurricular activities, etc. – essentially, a place “run by the people of Govandi and for the people of Govandi.”

Terri, on the other hand, is excited to welcome a strong new board for The Baobab Home, with whom she hopes to create strategic plans to make the organization more self-sustainable – so that in future difficult times, it can continue to be there consistently for the children and families of Bagamoyo.

At the end of the day, it is often down to the communities and organizations functioning within them to knit up practical safety nets that cater to children’s needs. “If you don’t intervene at the grassroots level, you cannot reach every child,” as Gargi believes. “The impact [of COVID] is so varied, so complex. Every child has suffered in a different way to a certain extent, especially psychologically. It is very important to have some sort of on-the-ground engagement because that is the only way you will be able to really offer the support that the children need.”