On the coast of Batangas, liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals and gas-fired power plants are projected to nearly triple. A mix of pipelines, jetties, and tankers would soon accumulate in the Verde Island Passage—a center of marine biodiversity. As the Philippines pushes forward with its vision to become an LNG Trading and Transshipment Hub for the Asia-Pacific region, locals find themselves at a crossroads.

(This is the first installment of Diinsider Life’s “Murky Waters”, a two-part series on the socio-environmental threats in Verde Island Passage and the subsequent initiatives locals are taking to solve them.)

A ‘mad dash for gas’ in the region

LNG terminals and gas-fired power plants are expected to nearly triple in the following years, pointing to a major and rapid build-out for natural gas infrastructure in the region.

Map of gas build-up in Batangas | via “Philippines: LNG Boom in the Verde Island Passage” (Gogel, 2023)

Five such plants are currently operational, with eight more in various stages of development. The LNG terminal landscape is equally concerning, with one already functioning, two under construction, and six more in the proposal phase.

Multinational companies such as Atlantic Gulf & Pacific, First Gen Corporation, and San Miguel Corporation own the facilities.

The impact on local communities is already felt. Fish catch dropped and promised financial assistance remains to be seen, according to residents in the area.

“When I was younger, I would catch more than five kilos of fish,” says Maximo to investors of Europe-based UBS Group, which lends support to a gas-fired power plant in Batangas. “Now, we receive less fish from our seas.”

Considering everything in the pipeline, 85 to 128 LNG tankers are projected to hit the waters within 2024, increasing the risk of spills and leaks. That number goes up to 387 by 2027 should all proposed facilities go online.

Angelica Dacanay of Center for Energy, Ecology, and Development (CEED) notes how tankers have exclusion areas, further minimizing the spaces where fisherfolk can catch fish.

The facilities also pose multiple threats to marine life, including coral damage from hot water discharge, ecosystem disruption due to coastal alterations, and the risk of importing invasive species via a growing number of tanker ships.

Health concerns have also emerged. LNG terminals release air pollutants that can contribute to respiratory disease, heart disease, and cancer.

“Almost 4,000, with kids under five counted at over 2,000 from 2017 to 2021 are struggling with respiratory infections and cardiovascular diseases due to ‘dirty air’ caused by fossil gas plants in Batangas,” the Philippine Movement for Climate Justice said in a statement.

While the Batangas City Health Office has so far found “no evidence-based data” directly linking the health issues to the power plants, they admitted the matter requires further investigation.

Despite these concerns, the national government considers natural gas as a transition fuel, with aspirations of becoming an LNG Trading and Transshipment Hub for the Asia-Pacific region.

“We just have to make our best choice which is natural gas,” says Rino Abad, the fossil fuels director at the Department of Energy, describing it as clean and less expensive. “We cannot increase our energy capacity by renewable energy alone.”

Energy experts and environmental advocates challenge this. While natural gas does produce 20% less carbon dioxide than oil when burned, it is not a clean nor renewable energy source.

The primary concern lies with the main component of natural gas—methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. Methane has a warming effect over 80 times that of carbon dioxide in a 20-year timeframe.

From extraction to transportation, liquefaction, and re-gasification, the LNG lifecycle can produce greenhouse gas emissions nearly equivalent to those released during the actual combustion of the gas.

“Massive LNG expansions will seriously compromise meeting the 1.5-degree Celsius Paris Agreement goals,” argue climate specialists Jamie Lee and Mima Holt.

Investing heavily in LNG infrastructure could lock countries into fossil fuel dependence, potentially undermining efforts to transition to renewable.

The Philippines’ energy mix in 2020 was composed of 47% coal, 24% renewables, 22% natural gas, and 6.2% oil-based energy.

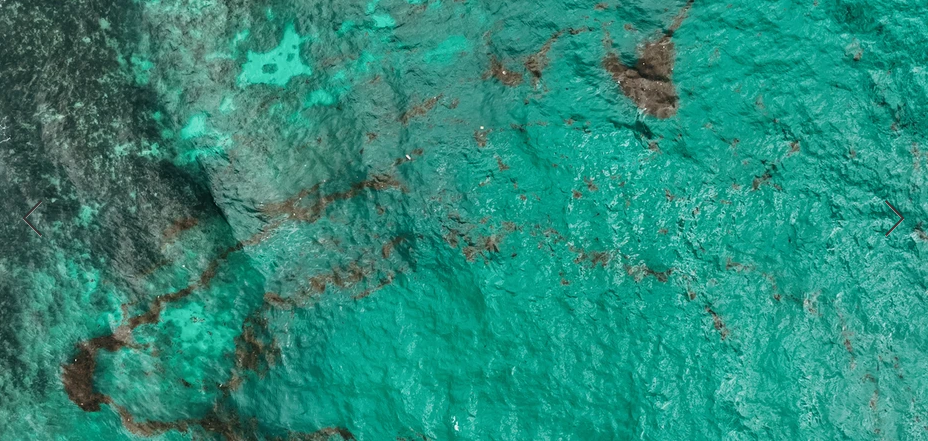

Meanwhile, the waters of Verde Island Passage, dubbed the ‘Amazon of the oceans’, bear the scars of environmental neglect. Oil slicks mar its surface, even a year after the Mindoro oil spill which is one of the largest in Philippine history.

The waters of Verde Island Passage after a major oil spill | via Jilson Tiu for CEED

The waters of Verde Island Passage after a major oil spill | via Jilson Tiu for CEEDThe lingering hold of Mindoro oil spills

Tanker MT Princess Empress capsized off the coast of Mindoro, releasing 900,000 liters of industrial fuel into the Verde Island Passage dubbed the ‘Amazon of the oceans’.

Damages stretched across 120 kilometers, contaminating at least 14 marine protected areas and halting the livelihoods of nearly 28,000 fisherfolk.

The oil spill coated coral reefs, mangroves, and seagrass beds in a thick, tar-like substance, smothering ecosystems vital to marine health. UP Marine Science Institute estimated a total of 36,000 hectares were likely affected.

The disaster’s impact seeped into every aspect of coastal life, from the stench locals wake up to in the morning to the dinner tables at family households.

More than 200,000 people were affected across the provinces of Batangas, Oriental Mindoro, Occidental Mindoro, Palawan, and Antique.

It was later found out that the tanker had no permit to operate despite having sailed nine times prior. Cleanup operations were conducted, but the spill has a lingering effect.

According to fisherfolk, daily yield is down 1-3 kilos even after nine months elapsed and the fishing ban was lifted. The total estimated damages from that singular spill is P41.2 billion, of which P1.1 billion are losses in fishing income.

Remnants of oil and grease can still be seen in the waters of VIP today. As of January 2024 – nearly a year after the spill – only two out of nine marine protected areas passed water quality checks.

Smaller oil sheens and slicks occur regularly due to discharges from other ships.

In August 2023, a fishing vessel carrying 70,000 liters of diesel sank due to Typhoon Saola. Another sank just a few days later.

As the main shipping route between the major Philippine islands, the VIP saw 76,226 annual vessel calls between Batangas, Mindoro, and Marinduque alone. The number is forecasted to rise as LNG facilities grow.

In response to mounting threats facing the Verde Island Passage, representatives from Protect VIP fly out of the country—protesting before groups bankrolling the gas projects impacting their very lives.

READ PART 2: Filipino fisher flies internationally to protest fossil fuel financing