A fisherman from oil-slicked Batangas flew to Europe and Japan to protest before companies financing fossil fuel projects along the Verde Island Passage (VIP). Sixteen gas facilities are expected to rise, despite one of the largest oil spills occurring in the area just last year.

“I am most afraid that my children and grandchildren would ask me… why didn’t you do anything about it?” says Maximo Bayubay, vice president of fisherfolk group Bukluran ng Mangingisda sa Batangas—right before boarding his first international flight.

(This is the second installment of Diinsider Life’s “Murky Waters”, a two-part series on the socio-environmental threats in Verde Island Passage and the initiatives advocates are taking to solve them.)

READ PART 1: Natural gas build-up endangers coastal residents in the Philippines

Protecting the ‘Amazon of the oceans’

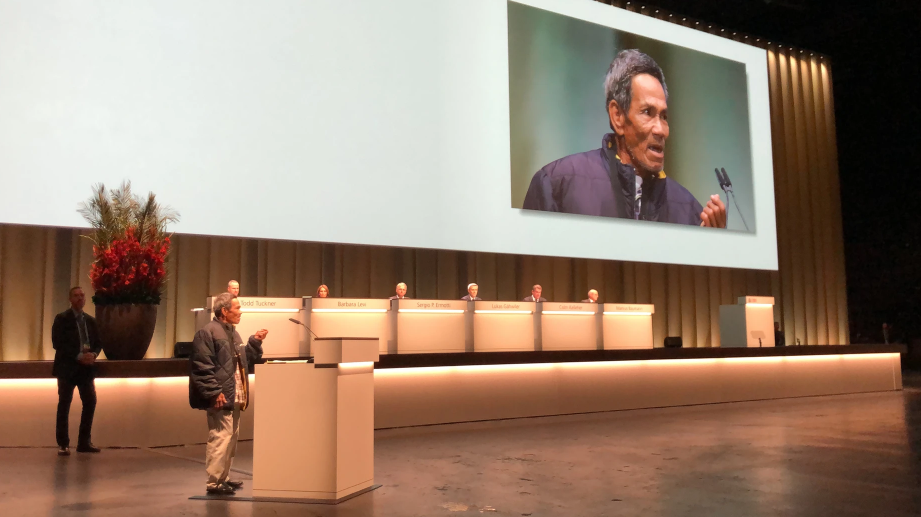

In response to oil spills and gas build-up in the Verde Island Passage, Maximo spoke before investors and shareholders of European financial giants UBS Group and Standard Chartered at their annual general meetings last April.

“We are suffering now and you are continuing funding, financing fossil gas. It’s a big question for me. Why?” he asked during an 8-minute speech. “What will we promise them [the future generation] if we continue financing this?”

Maximo addresses UBS Group about fossil fuel financing in the Philippines | Screenshot via Protect VIP

Maximo addresses UBS Group about fossil fuel financing in the Philippines | Screenshot via Protect VIP

The said banks are among the biggest financers of San Miguel Corporation (SMC).

San Miguel and its subsidiaries are developing gas plants along the Verde Island Passage—a million-hectare biodiversity hotspot dubbed the ‘Amazon of the oceans’.

Many of the gas plants and LNG terminals in the area are owned by companies like San Miguel, Shell, and Atlantic Gulf & Pacific (AG&P), which get their funding from institutions miles away from VIP waters.

Separate meetings were later held with fossil fuel financers in Germany and Austria, likewise invested in gas projects along the VIP.

Maximo also spoke at a press conference in Tokyo weeks later.

The Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) and Osaka Gas jointly invested 100 million dollars in AG&P, which recently completed a publicly-disputed LNG import terminal in Batangas via its subsidiary.

Several Japanese institutions also provide funding to gas projects in the VIP. Among such banks are Mizuho Financial Group, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, and Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation, which Maximo was also slated to meet.

“We the fisherfolk in the VIP are facing a very difficult life,” Maximo admits. “Aside from declining fish catch, fossil gas [projects] are sprouting here and there, producing very dirty emissions that are dangerous to human health and polluting the Verde Island Passage.”

Maximo’s call is part of a larger movement.

He flew in alongside representatives from Protect VIP, a coalition of advocates, communities, fisherfolk, NGOs and civil society groups committed to safeguarding the Verde Island Passage.

“What we’re trying to do is stopping the money pipeline,” shares Angelica Dacanay of the Center for Energy, Ecology, and Development (CEED) who flew with Maximo to Europe. “If there’s no money flowing into the gas power plants or gas developers, they wouldn’t be able to proceed with the projects.”

Since their international campaign, three major financial players took steps to distance themselves from fossil gas investments in the Philippines.

German asset manager DWS publicly stated that they divested from San Miguel Corporation. BNP Paribas, a French bank, declared to Protect VIP that financing fossil gas in the Philippines is not part of their strategy. Austria-based Erste Bank also informed them in a closed-door meeting that they divested from San Miguel.

“They now understand the problem on the ground. They admitted that they are unaware of the issues,” Maximo reports. “Now that they know, I believe they will listen, as long as we remain united and continue our fight to protect the Verde Island Passage.”

Tactics that made it possible

Protect VIP representatives posed ecological threats as reputational, legal, and financial risks, speaking directly to investors’ bottom line.

For instance, both AG&P and San Miguel projects face complaints for violations of local and national policies such as illegal tree cutting and lack of proper permits.

Violations span a range of environmental and land use regulations, including the Revised Forestry Code, Coconut Preservation Act, Water Code, the Department of Agrarian Reform’s land use conversion rules, and the presidential decree establishing an environmental impact statement system.

In December 2023, fisherfolk and environmental groups lodged a complaint with JBIC, prompting the bank to investigate.

Local fishers carry a banner protesting fossil fuel financing by JBIC | Photo via Protect VIP

“We were raising this to the financers because they have their own due diligence,” Angelica shares. “The financers are also doing their part in terms of checking and monitoring.”

Some projects lacked a power supply agreement which would allow it to supply energy to the national grid.

“That would mean no assurance or no sustainable profits for the investors,” Angelica reports. “We’re raising these concerns to financial institutions because it increases their exposure to reputational risk.”

San Miguel’s involvement in the 900,000-liter Mindoro oil spill, with damages valued at P41.2 billion, further underscore these risks.

The trips were built upon an earlier effort in May 2023, when Protect VIP first ventured to Europe in the wake of a 900,000-liter oil spill.

During the initial visit, environmentalist Fr. Edwin Gariguez stressed the VIP’s ecological value and invoked the recent oil spill to contest fossil fuel projects in the area. Meanwhile, the recent tours with Maximo at the center aimed at driving home socio-economic costs of continued investment.

“It was a very important story to tell since it is a human story,” Angelica notes, raising the importance of grassroots-led storytelling. “We needed to directly tell them how the livelihoods of fisherfolk and people in the VIP are depending on the resources around the area.”

Their international trips owe much to collaboration with local groups abroad.

Europe-based Urgewald, BankTrack, and Fossil Free Finance Campaign accompanied Maximo during the Europe trip, while Friends of the Earth Japan helped them acquire professional interpreters for the visit in Tokyo.

Funding for the trips also came from the collective effort of various local and international groups. “It wasn’t a one-time, big-time funding,” Angelica notes. “It was a concerted effort of the whole Protect VIP network and our international allies.”

List of Protect VIP network | via Protect VIP

Between in-person tours, Protect VIP maintains pressure through online engagements.

“As part of the overall campaign, we’re engaging with different banks and financial institutions every chance we get, online or offline,” Angelica says.

‘Financing is just one part’

Protect VIP operates simultaneously at local, national, and international levels.

“We’ve always understood that protecting the Verde Island Passage requires action at all levels,” Angelica affirms.

Back in the Philippines, Protect VIP pursues legal interventions to secure full compensation for communities affected by the Mindoro oil spill. They also push for the inclusion of the Verde Island Passage in the Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System (E-NIPAS).

Locally, CEED conducted regular water quality assessments to monitor toxic chemicals from oil spills and fossil gas developments. Of the nine marine protected areas, only two passed quality checks.

Protect VIP is currently filing a petition for a writ of continuing mandamus with the Court of Appeals against the Department of Natural Resources for failure to maintain water quality in marine protected areas.

Angelica concludes, “The financing is just one part.”