By Kyaw Nyunt Linn

COVID-19 pandemic has been changing our day-to-day activities since the beginning. Water becomes an essential element, and access to clean water is crucial to reducing the risk of COVID-19. In addition, the regions where water insecurity pre-exists before the pandemic increased the need for clean water to wash hands.

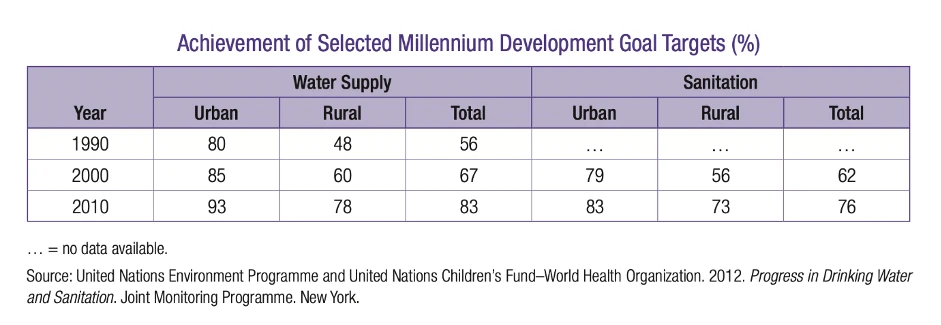

Water services cannot cover a large proportion of the urban and rural population. According to the document“Myanmar Urban Development and Water Sector Assessment, Strategy and Roadmap” published by Asia Development Bank (ADB) 2013, the percentage of people using an improved drinking water source is characterized as 83% overall (urban 93%, rural 78%). However, the quality of water is debatable, as piped water supply systems in the main cities involve untreated surface water from reservoirs based on the Joint Monitoring Programme definition. As a result, most people in urban areas depend on untreated private water supplies, which is questionable if it meets bacteriological guidelines for drinking.

Regarding the pre-existing water insecurities, COVID-19 impacts exacerbate water insecurities and make it more serious. The researchers from the Sustainable Mekong Research Network (SUMERNET) identified effective ways to enhance access to clean water for drinking and hygiene of marginalized, vulnerable people in Myanmar by listening to their stories of how they have been reacting to the impacts of the COVID-19 outbreaks. The research was done in three regions selected based on geographical locations – Pindaya township, located in the mountainous region of Shan state, Bogalay township, situated in the delta region and Seikkyi Kanaungto township, a peri-urban area of Yangon city.

Affordability, quantity, and quality

“Normally, people in Bogalay use water from the stream for domestic purposes. Some are using groundwater while some cannot afford to dig a 600-ft underground well which can cost around 1,500,000 kyats (approximately 850 USD) to access the water,” Dr Nilar Aung, a lead researcher from SUMERNET, explained the pre-existing conditions of water insecurity in the region.

Although water quantity is not an issue in the delta region, the vulnerable community is already experiencing water quality issues for drinking and personal hygiene practices. They usually use stream water for cooking and drinking despite water quality being inappropriate for health. People wash their hands with this poorly treated water for the prevention of COVID-19.

Based on the report “UN-Water Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking-Water” published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2015, 34.5% of the population perform water treatment at home, and those treatments are carried out by cloth by 76.2%, boiling by 1.4% and filtering by 0.6%. These figures indicate that water treatment is relatively low.

Meanwhile, in Seikkyi Kanaungto Township, located in the southern part of Yangon city, people are face issues related to water quantity and affordability. The township is mainly rural, underdeveloped; and informal settlements are being formed. “Every summer, water shortage usually occurs, and people are heavily relying on water trucks donated by the patrons or philanthropists before the pandemic,” said Dr Nilar. The quantity of clean water is scarce, even when they get access to clean water. Informal settlement groups have more experience with water shortage than others, so they have to use water from the Yangon River and ponds for drinking during the period of COVID-19.

In Pindaya township, located in the mountainous region of Shan state, the government can only provide water by filling the concrete storage tank somewhere in the middle of the village. People have to fetch water by themselves in line with COVID-19 guidelines. “The local people in this area understand the value of water due to the recurring water shortages, but they require capacity and knowledge to improve water security,” Dr Min Oo, a research assistant who engaged with locals in Pindaya, shared his experiences. He conducted interviews with local authorities and online surveys to assess the research.

From his interview with a local expert, most locals don’t think to oblige the rules due to the quantity of water they retain. “They usually re-use the masks without even rewashing them and cannot afford new masks because of their poor income,” he explained based on the interaction with the local community. Even the locals exposed to someone with COVID-19 routinely go to the communal lake where all the people in the vicinity rely on for domestic and personal use. Consequently, the locals have double pressure on their water security during the pandemic.

The hindrances among marginalized and vulnerable people

The government have organized programs to mitigate the impacts of COVID-19, such as educational talks, knowledge sharing in terms of articulation, and awareness of the pandemic. Based on the interviews conducted by the researchers, the most effective way to educate the locals is by amplifying the awareness of how to handwash and use hand gel and masks through social media. COVID-19 education and updated information, including confirmed cases and death tolls, were regularly announced to local people twice a day in the downtown area.

Nevertheless, the locals are reluctant to oblige to the COVID-19 restrictions as they struggle to get minimum incomes in their daily lives. Most marginalized and vulnerable people are do not have access for receiving government support regarding valuable information and medical equipment.

According to the surveys performed by the researchers, respondents who were more socially insecure were more likely to be facemask washing water insecure and handwashing water insecure. Therefore, social relations are imperative for access to water for washing.

Unaware respondents who claimed to have “never heard of COVID-19” can be found in upland, in this case, Pindaya. Thus, inhabitants are less likely to adopt good handwashing practices as a consequence of less exposure to public health campaigns in remote locations.

“People from the upland are using water from the communal lake for multiple reasons such as domestic purposes, farming, personal hygiene and drinking purposes. That’s why they value their lakes but don’t know how to work together and manage to improve water security in an integrated way,” Dr Min Oo stated his thoughts on local capacity.

“Due to being used for multiple purposes, the quantity and quality of water are deteriorating. Therefore, enhancing the local knowledge capacity in a collaborative way can improve the water security, which can be helpful for unprecedented crises like the COVID pandemic,” he suggested.

The research and writing of this piece was made possible by SUMERNET 4 All Media-Research Partnerships Fund from Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI).

Check out more on “COVID-19 and household water insecurities in vulnerable communities in the Mekong Region” (SUMERNET)