By Zhouai Joann Yu

“Ecuador has 30% of our energy production based on hydropower. Sounds good right?” says Emilio Cobo, an environmental engineer and founder of the Andean Rivers Observatory, an organization monitoring water infrastructure in the Andean region.

Hydropower is portrayed as one of the leading “clean” energy options, yet the true effects of each project are much more intricate. While most hydropower projects have immense potential to reduce fossil fuel dependency, the influences of such large infrastructure on rivers and surrounding areas can be unpredictable.

The Coca Codo Sinclair dam in Ecuador is representative of the possible facets of an impactful hydropower project.

History of Coca Codo Sinclair

Before the early 2000s, electricity supply shortages plagued Ecuador. Many cities experienced rolling blackouts, while the national electric grid did not reach rural areas. To rectify the country’s energy deficit, the central government of Rafael Correa (in office 2007-2017) designed an aggressive energy transition agenda characterized by the construction of hydroelectric power plants.

The centerpiece of the president’s plan, Coca Codo Sinclair, was signed into reality in October 2009. The Ecuadorean state-owned Cocasinclair entered a 2.2 billion USD turnkey contract with Sinohydro Corporation, one of the key subsidiaries of the Power Construction Corporation of China.

Sinohydro was responsible for the engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) of Coca Codo. One year after signing the contract, in June 2010, a credit agreement was negotiated when China Eximbank provided a loan of 1.7 billion USD to cover 80% of the total cost.

Construction of the dam began in July 2010, with the operational launch on November 18, 2016 – around 10 months later than the stated deadline. Since then, Coca Codo continues to operate as the largest hydropower plant in Ecuador.

Positive impacts

The positive effects of Coca Codo Sinclair are undeniable.

The construction of the dam boosted the local economy and the electricity generated by the plant ameliorated two issues – dependence on fossil fuels and faulty electricity supplies.

“Before Coca-Codo was built, it [electricity supply] was incredibly unstable,” says Julio Pérez, the former mayor of El Chaco. “Across El Chaco, the lights in homes and businesses would constantly flicker on and off.”

Coca Codo has remedied the problem. Pointing to the ceiling of his own house, Pérez confirms that since Coca Codo strengthened the supply to the electrical grid, households across El Chaco have not experienced blackouts.

Electric lines run along the Coca River, connecting the hydropower generators to the electric grid

Beyond local benefits, Coca Codo has also significantly diminished fossil fuel usage. The installed capacity of hydroelectric power in Ecuador in 2017 was approximately 81% higher than in 2007, with those numbers expected to rise. Currently, Coca Codo Sinclair produces around 30% of Ecuador’s electricity.

“No matter what other effects Coca Codo might have had, it seriously reduced our dependence on coal and oil,” says Diana Castro, Head of Research at the Latinoamérica Sustentable (LAS), an NGO that seeks to bridge divides between Chinese energy companies and local Ecuadorean communities.

El Chaco benefitted from the economic impacts of the dam as well

According to official data from Cocasinclair’s parent company, the Electric Corporation of Ecuador (CELEC), the hydropower plant generated 6,000 direct jobs and 15,000 indirect jobs during the construction phase.

Before the construction of the dam, a large majority of El Chaco earned their income through agriculture and livestock. According to Pérez, an average resident would earn about 115 USD per month. However, he continues that depending on the type of work done for Sinohydro, local wages rose greatly, varying between 600 to 800 USD per month.

The construction of the Coca Codo Sinclair Dam (above) lasted six years

Furthermore, according to Pérez, Sinohydro provided skills training to all local workers. Workers who had no previous experience were given lessons on industrial security and how to safely manage heavy machinery; the company also provided training sessions that specialized in skills specific to the construction of a major hydroelectric dam.

Negative impacts

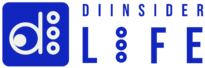

A large challenge to Coca Codo is the erosion of the San Rafael cascade and the riverbanks of the Coca River.

In February 2020, four years after the inauguration of Coca Codo, the tallest waterfall in Ecuador collapsed. Many environmental scientists believe that Coca Codo prompted the event.

The San Rafael Cascade had been continuously eroded in the middle, leading to its collapse

Damming a river slows its flow, giving it less kinetic energy to carry sediment. Since the river is unable to carry the usual sediment, it sinks to the bottom.

When the river water flows over the dam while the sediment, having sunk to the bottom, is blocked by the structure, a phenomenon called “Hungry Water” is created.

Hungry Water occurs when a river has the power to transport more sediment than is available. It then seeks dynamic equilibrium by eroding the downstream river bed to compensate.

San Rafael was a victim of hungry water. The water that ran through the dam contained less sediment than before, resulting in the erosion of San Rafael and the Coca River.

Since the collapse of the San Rafael Cascade in 2020, erosion downstream of the Coca River has accelerated

“It would have been a mega coincidence,” says Cobo, “since the waterfall has been there 8000 years, yet after just four years of a dam implemented upstream, the waterfall collapses”

Not all experts agree.

Alfredo Carrasco, a geologist and former secretary of Natural Capital at the Ministry of Environment, argues that the disappearance of the waterfall was natural.

“I had predicted in 1987 that the waterfall would someday disappear due to erosion,” says Carrasco. He believes that four years was not enough time for Coca Codo to impact San Rafael.

Cobo agrees that the natural erosion of San Rafael would eventually have caused a collapse. However, he maintains that the dam greatly accelerated the process.

“The problem is, none of us have any evidence,” says Cobo. “They are all hypotheses and theories because no one monitored the river before building the dam, so there is no data.”

San Rafael was not the only natural structure affected: the river banks of the Coca River have been eroded too.

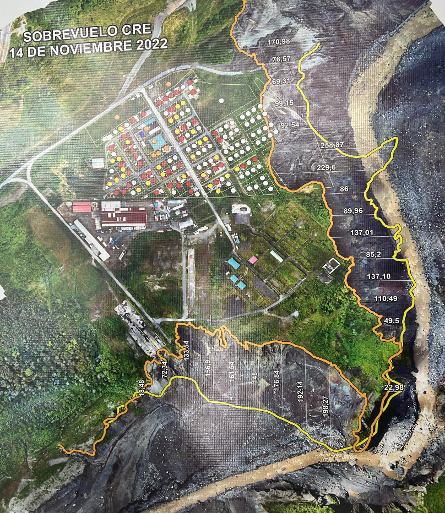

According to the local municipality of El Chaco, 90 families from the San Luis and San Carlos communities are at risk due to the extreme erosions of the banks of the Coca River.

“My house was 600 meters away from the river, but due to the erosion, it is now only 150 meters. Once 50 meters, the government will make me move,” says Nancy, a resident of San Carlos.

Nancy, outside of her convenience store

The local government of El Chaco has been pushing for the people to abandon their perilous communities, yet the move has been met with resistance.

“People know the risk in San Luis but they literally cannot afford to move,” says Javier Chávez, the current mayor of El Chaco.

Nancy owns a small convenience store that serves as her main source of income. Once it is too dangerous for her to live in San Carlos, she will live with her relatives in a nearby city. However, members without other options are moved into social housing or small rental residences, with little help from the government.

Financial difficulties trouble the local communities. “We just have to start over. Yes, it will be very hard, but we have no choice,” says Nancy.

Map tracking the erosion near San Carlos; Yellow: 2020, Orange: 2022

Apart from erosion of the natural structures, man-made and crucial infrastructures are also at risk.

Critical roads for the transportation of produce and livestock have been destroyed due to erosion. Pipelines near the Coca River from Crudos Pesados Oil Pipeline (OCP) and Trans-Ecuadorian Pipeline Systems (SOTE) have also broken under pressure, with the oil spills causing further environmental damage.

There used to be a road near the river; in the wet seasons, rising water levels and erosion destroyed the road

Local communities have been affected at every level. Although San Carlos is on the left bank, many farms are on the right. Since erosion had broken the bridge that connected the two, many locals have been unable to access their farms.

The economy has been heavily impacted, as agriculture is the main source of income for families. “Yes, economically it is very hard. But emotionally too. This is my home,” says Nancy.

The dam is also unable to operate at full capacity.

Although designed to operate at a capacity of 1500 Megawatts, the powerplant fails to meet such standards. Instead, its capacity usually varies between 800 and 1000 Megawatts. Carrasco explains that due to the geography surrounding the dam, there is not enough water flow for Coca Codo to operate at a high capacity.

Coca Codo Sinclair Dam, 2023

Some blame faulty policy-making for the many issues.

Many of Ecuador’s environmental policies have not been updated since the 1980s.

However, another problem is the enforcement of policies. “The ministries of Ecuador are very weak,” says Diana Castro. “When pressure comes from the central government, the ministries often give away.”

Coca Codo is such a case. Although the dam obtained environmental licensing, the approvals were rushed. Carrasco explains that the design of the dam was based on studies from the 1980s, which were quickly updated within two weeks. As a result, the structure and placement of the dam failed to account for nearby seismic activity and water flows.

Alternatives

Experts are exploring solutions and alternatives to Coca Codo.

Ideas of modification are floated as solutions. For example, “bottom doors,” which are openings that are built into the base of the dam, allow the sediments that have sunk to the bottom of the river to flow through, relieving the Hungry Water and restoring dynamic equilibrium.

Others suggest that Ecuador should leverage its potential for other renewable energy sources.

“Since 2000 there have only been two wind power projects from Chinese companies, while eight huge hydroelectric projects have been constructed,” says Diana Castro. Although the construction of all energy projects demands meticulous examinations of possible impacts, wind can sometimes be a “cleaner” option when compared to hydropower.

Ecuador also harbors strong potential for solar power, as the equator cuts through the country. Howev

er, Cobo is doubtful that there will be future developments in the solar sector, as experts emphasize the corruption in Ecuador when concerning large energy projects.

“The very centralized way of doing things in Ecuador is linked to corruption,” says Castro. “A very small group of people makes the big decisions when investing in energy.”

References

https://www.ariae.org/servicio-documental/electricity-sector-ecuador-overview-2007-2017-decade